|

The Sealed Shrine

Legacy, Succession, and the Sacral Usurpation of the O.T.O. after 1923

[AI-generated DIY instructions inspired by Theodor Reuss' Parsifal and the Secret of the Graal Unveiled] Dramatis Personae:

The death of Theodor Reuß in October 1923 triggered a crisis that shook the structural integrity of his Ordo Templi Orientis. At the heart of the matter stood an age-old and ever-current question of esoteric authority: Who holds the right to continue an occult legacy – the one who possesses the symbols or the one who knows how to interpret them? During his lifetime, Reuß had made no clear provisions for succession. He presumably deliberately positioned several potential successors against one another in order to maintain his influence until the very end. Upon his death, three potential heirs emerged, each with a blend of formal legitimacy and symbolic claim: Heinrich Tränker, appointed in 1921 as X° for Germany; Charles Stansfeld Jones (Achad), holding the same office for North America; and Aleister Crowley, X° for the English-speaking countries, who had proclaimed himself O.H.O. in 1921 – without Reuß’s confirmation.

1. The Schism Begins: Reuß and Crowley The break between Reuß and Crowley had already occurred prior to the former’s death. Reuß accused Crowley of undermining the hierarchical order by equating the O.T.O. with the A∴A∴ and spreading public confusion. In a telegram to Spencer Lewis dated 9 October 1921, he was blunt: the connection to Crowley was “dissolved.” Whatever Crowley might do henceforth was “no longer any concern of the O.T.O.”

Crowley responded not with retreat but with a symbolic act

of self-empowerment. In his diary of 18 November 1921, he wrote: “I have proclaimed myself O.H.O.” On 23 November he elaborated: “I therefore accept the responsibility of this office and proceed to assume its Authority from this

moment.” His claim rested on The Book of the Law: “The slaves shall serve.” Historical legitimacy? Superfluous. Reuß’s age and merit, he conceded, deserved respect – but: “authority reposes on force. You are unknown outside an insignificant clique in a beaten and disintegrated nation.” (i.e., Germany)

[AI-generated image] Thus the central conflict was outlined: Crowley staked his claim on charismatic, performative authority, while Reuß, Tränker, and later Pauline Reuß insisted on documented succession, archival continuity, and proprietary rights. Crowley’s rhetorical flourish serves as a deliberate overwriting of institutional history. He replaces succession with proclamation, legitimacy with visibility. His silence on Reuß’s repudiation is a calculated whitewashing of history – a deletion by assertion. By speaking so much, he avoids saying what would undermine his claim.

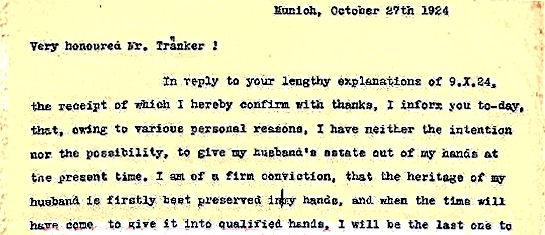

2. The Legacy as Power Instrument: Pauline Reuß 1923–1924 Clara Linke, Hans Rudolf Hilfiker’s lover and co-founder of a children’s home on Monte Verità, had been designated Reuß’s universal heir in a will dated 20 December 1922. After her sudden death in Rome, Reuß composed a new testament on 27 June 1923 in favor of his wife Pauline and his housekeeper. He died on 28 October 1923 – without naming successors in MM, G.K.K., or O.T.O. His first wife and son, born in 1879, received nothing. On 7 December 1923, Pauline Reuß and her sister Martha Gierloff formally accepted the inheritance. According to the probate file, “no close relatives” of the deceased were still living. There was no substantial estate – “neither a residual inheritance nor property” – but there was an esoteric archive: rituals, the Golden Book, the register of the order, correspondence, and the O.T.O. seal. In 1924, Heinrich Tränker sought access to these documents. In a report to Charles Stansfeld Jones, he described Pauline as “an old lady who had to count every penny,” critical of the order for having “done nothing during her husband’s illness.” He explained to her that in Germany, the order now existed “only on paper.” Despite her reservations, Pauline granted access to the materials: “manuscripts for films (?), that do not concern us [...] the Golden Book, the Register of the order, divers charters, correspondence of the last few years [...] rituals that in various degrees had not yet been finished.” Tränker was relieved: Reuß had designated no successor, nor issued any higher patent for Germany. A gap he was eager to fill. But just days later, Pauline demanded the documents be returned. In a letter dated 4 October 1924, she wrote: “I am solely interested in ensuring that the only thing my husband left behind goes into good and trustworthy hands.” She confessed to “no great sympathy for the whole matter,” citing bitter experiences over the previous years. On 28 October she wrote more firmly: “For various personal reasons, I currently have neither the intention nor the possibility to give up my husband’s estate.”

Tränker withdrew – not from insight, but resignation. To Jones, he wrote laconically, “Frau Reuß has no idea about the O.T.O. […] The legacy is worthless – aside from the historical evidence.” She thus became the “keeper of the signs without an office”: custodian of the power symbols, with no ritual function.

[AI-generated image] Pauline Reuss’s insistence on trustworthiness masks her refusal to cede control. Her silence on any specific successor is deliberate: by denying transfer, she retains dominion. Her moral high ground becomes a strategic refusal. What she withholds is not just paper – but authority itself.

3. Authority Without Possession: Tränker, Jones, Crowley While Pauline blocked access, Tränker sought legitimacy elsewhere – mainly through international correspondence. In letters with Charles S. Jones, both confirmed that their Charters were “in perfect order.” Yet Tränker declared unequivocally that the O.T.O. held “no particular value” for him (letter to Jones, 8 March 1924). He preferred to operate behind the scenes. The public rôle, he suggested, should go to Crowley or Jones. The latter declined politely. Crowley, characteristically, accepted immediately. Tränker’s posture of detachment conceals a quiet ambition. His declared disinterest sits uneasily with his attempts to mediate between Jones and Crowley and his continuing use of the title O.H.O. He seeks validation – but not the burden of leadership. He wants influence, not visibility. In a letter to Tränker from November 1924, Crowley wrote: “It is my True Will to spread the Law of Thelema, and for this purpose, I wish to take control over all existing movements.” The other leaders, he added, were too weak – “they all fear that I will expose them as frauds.”

4. Weida 1925: Attempted Reconciliation – Eventual Collapse In June 1925, Tränker invited Crowley to the “Weida Conference” – a final effort to forge unity. Crowley was initially welcomed with messianic fervor: the “Testimony of the Seekers” named him “Teacher of the World.” Signatories included Tränker, his wife Helene, Karl Germer, Leah Hirsig, Norman Mudd, Dorothy Olsen, Martha Küntzel, and Otto Gebhardi. Within days, the edifice collapsed. The Tränkers retracted their signatures. The pantry was locked. Crowley complained of “astral attacks” (brought on by hunger?). Germer, who had financed Crowley’s trip, was rewarded with the IX°. Tensions exploded. Crowley accused Tränker of having “utterly destroyed” his work – alleging tampered printing plates. Tränker countered, branding Crowley a “dangerous fraud” and “astral polyp” (letter to Gustav Meyrink, 5 December 1925). What began as esoteric convergence ended as tragicomic farce – involving sanctified egos and sealed food cabinets.

5. The O.T.O.’s Fragmentation into Competing Lines After Weida, the fragile network disintegrated. Albin Grau called for Tränker’s resignation. Eugen Grosche founded the Fraternitas Saturni. Karl Germer aligned fully with Crowley. Tränker continued publishing under the title “O.H.O.,” but his symbolic capital was spent. Jones, by then disillusioned, wrote (18 March 1925): “I look upon Therion as one of the worst enemies of His own teachings.” Tränker replied on 16 April: “To control all existing movements is a matter, with which I would scarcely want to have anything to do with.” Each faction claimed inheritance – yet none could fully embody it. Possession, performance, and persuasion collided – but none resolved the legitimacy gap. The order became a constellation of disconnected claims.

6. Epilogue: A Legacy Without Heirs Following Reuß’s death, the O.T.O. devolved into regional claimants, each wielding fragments of the legacy, none possessing it whole. The documents remained contested; legitimacy was perpetually deferred. Pauline Reuß preserved the archive – yet withheld access. Tränker sought legitimacy – and lost his following. Crowley claimed succession without paperwork – and triumphed, somehow. In 1950, young Swiss O.T.O. aspirant Hermann Joseph Metzger feared that Tränker might hold documents that could jeopardize him. During a visit, Metzger reportedly took home a pile of papers – and never returned them. Eugen Grosche warned Metzger: Tränker was “our fiercest opponent” (letter of 27 October 1950). But Tränker, too, possessed only fragments of the archive. Another part – including the fabled Yarker Charter – surfaced in the estate of Swiss Freemason Hans Rudolf Hilfiker, partner of Clara Linke. In a letter to Constant Chevillon dated 14 April 1936, Hilfiker wrote that the Charter had been “endorsed in my name as his authorized successor.” A certain lady – presumably Linke – was to deliver it, but died en route – nearly at the same time as Reuß. The Yarker Charter (24 September 1902) elevated Reuß to high degrees (30°, 31°, 33°, “Sovereign Grand Inspector General”) but did not grant global authority. Hilfiker concluded dryly: “L’O.T.O. est mort avec Reuss.” The order, he advised, should be “considered non-existent.” Hilfiker was both archivist and skeptic. He guarded documents he did not claim to understand. His silence masked a weary detachment. Unlike Crowley or Tränker, he neither sought followers nor recognition. His rôle was preservation – not proclamation. Pauline Reuß had the clearest vision: possession entails responsibility, not dominion. Tränker had fragments of the archive, Hilfiker the charters, Crowley the stage, Jones the doubt. Reuß left no heir – and in doing so, perhaps issued his most lasting initiation: a crisis in which esoteric authority could no longer be inherited, only contended.

What remained was a shadow order – fragmented, conjured,

mythologized.

O.T.O. Phenomenon navigation page | main page | mail What's New on the O.T.O. Phenomenon site? |

|

|

|