Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua

Fraternitad Rosa-Cruz

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller

|

|

Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua

|

|---|

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller

|

|

|

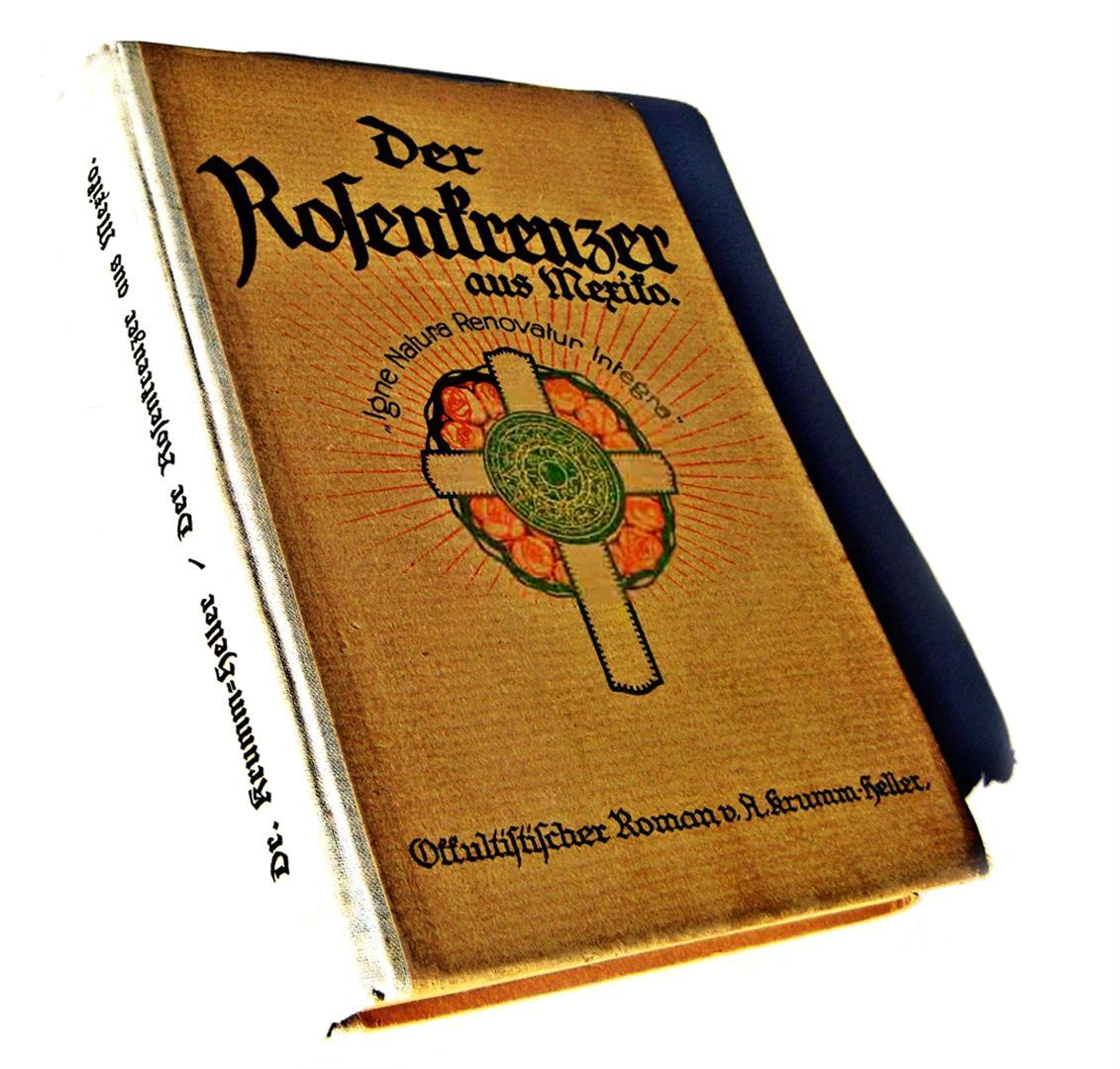

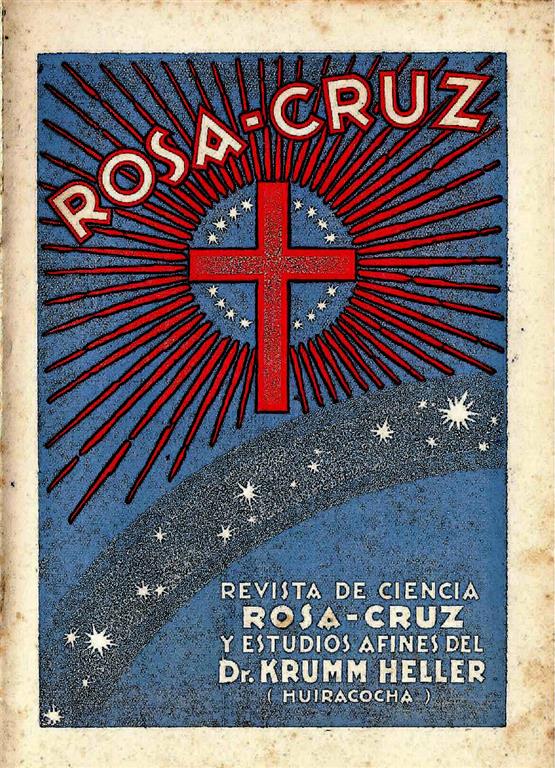

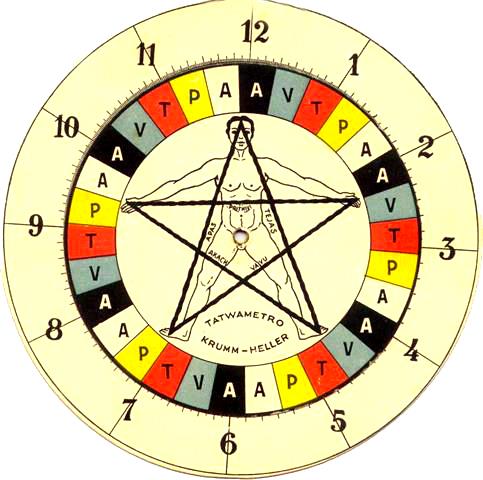

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller (1879–1949), who styled himself “Huiracocha,” constructed a belief system best described as a syncretic form of Gnosis overlaid with Rosicrucian elements. At its core lay a sacramental Gnosis with a pronounced Christological dimension: Christ was understood less as a historical figure than as a cosmic healing force. Around this, he wove the legacy of the Rosicrucians, theosophical concepts, fragments of Masonic ritual, and popular practices such as astrology, rune magic, and a deliberately “non-Jewish” version of Kabbalah. He insisted that true Gnosis comprised both science and religion, that belief must follow from understanding, and in 1927 he presented his Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua (F.R.A.) as a supra-confessional body offering a universal initiation through a curriculum of courses on metaphysics, zodiacal magic, runes, Kabbalah, thaumaturgy, and related subjects.

In his writings and organizational work Krumm-Heller appeared as a charismatic hierophant moving between Europe and Latin America. He cast himself as doctor and healer, as adventurer, and as cultural mediator between European esotericism and a South American heritage. At the same time he posed as a cosmopolitan networker — linked with Theodor Reuss, Gérard Encausse (Papus), Franz Hartmann, and Aleister Crowley — and as a national-revolutionary protagonist in Mexico, styling himself explicitly as Mexican and stressing his proximity to Francisco I. Madero and Venustiano Carranza in the 1910s, with Carranza until his assassination in 1920. Madero, the liberal reformer and president of Mexico from 1911 until his murder in 1913, was for Krumm-Heller a personal friend of eight years’ standing. He recalled having tried, in vain, to arrange Madero’s escape aboard a Cuban warship before his betrayal and execution, a “fratricidal crime” that compelled him to resign his university post in protest. Carranza, who assumed revolutionary leadership after Madero’s death and became provisional president, drew Krumm-Heller into the revolutionary struggle with both medical and military responsibilities. He rode at Carranza’s side into Mexico City in 1914, at the symbolic end of Porfirio Díaz’s 35-year dictatorship. His book Für Freiheit und Recht, written 1918 during his service in the War Ministry under José Almaraz-Harris, describes with patriotic fervor his activities as military doctor, propagandist, and field officer. He supervised field hospitals, performed thousands of operations under battlefield conditions, organized troop reviews, fought epidemics with improvised public-health measures, and even conspired to rally towns like Guanajuato to the Carranzist cause. Almaraz-Harris, in his preface, praised him as a “true revolutionary against despotism and the rule of a privileged minority”. From Krumm-Heller’s perspective, this was revolution with body and blood, fought with weapon in hand as much as with the scalpel or the printed word. Against that backdrop, one suspects he regarded his European occult correspondents — Reuss with his intrigues, Hartmann with his theosophical musings, even Crowley with his self-dramatizations — as armchair revolutionaries, dilettantes of paper and lodge-rooms compared to his own ordeal in the Mexican civil wars. Yet alongside this sacral persona he cultivated another voice: that of a polemical publicist, unafraid to issue antisemitic tracts and to declare his fascination with Hitlerianismo.

[AI-generated Image] The rituals, above all his Gnostic Mass (of his Iglesia Gnóstica, “Primitiva y Verdadera Iglesia Cristiana”), reveal Krumm-Hellers sacramental imagination: a Mass with the expectation of healing (testimonies, blessings, and prayers for healing). The Masses are Christocentric: they invoke Crestos or Cristo, employ bread and wine sacramentally, emphasize seven lights, repeat prayers of forgiveness, grace, and healing, and include reports of miraculous signs occurring during the celebration. Yet other figures — Isis, Nuit, even Baphomet — enter alongside Thelemic slogans such as “Amor é a lei, amor sob vontade” and “Telema.” The liturgy thus becomes a syncretic montage: Catholic formulas stand next to Egyptian invocations and Thelemic credos. Still, the theological core remains firmly Christological: Christ as cosmic soter and healer. The expectation of miracle and healing is integral to the rite and marks a sharp difference from Crowley’s Gnostic Mass, which relies on sexual symbolism and cosmic drama. His relation to Thelema is ambivalent. He absorbed Thelemic formulas, mottos, and imagery, weaving them into the F.R.A. rituals, and gave the impression of kinship with Crowley. Yet these borrowings are only surface grafts, fitted into his own gnostic-Christocentric framework without dogmatic commitment. His Gnosis remained ascetic and Christocentric, never libertine. This deliberate distance is critical: Krumm-Heller wanted not a Thelemic church of sexual magic but a sacramental Gnosis oriented toward healing and moral rectitude. The antisemitic dimension casts a shadow across his legacy. His pamphlets demonstrate his readiness to embrace the racialist and political discourses of his age. The rituals themselves rarely articulate antisemitism directly; their idiom is universal, gnostic, and Christian. But indirectly his ideology seeps through, in his privileging of runes, his avoidance of Jewish Kabbalah, and his construction of a supposedly “original,” Aryan Christianity. His system thus carries the imprint of political ideologemes, even if these rarely surface openly in the sacramental context. The question of originality versus compilation is unavoidable. Krumm-Heller was not simply a Crowleyan imitator. He was a selective importer, appropriating Thelemic vocabulary but embedding it in a more Christocentric, gnostic, and therapeutic liturgy. He was original precisely where he connected his Latin American experiences — healing practices, Amerindian motifs, revolutionary politics — to a sacramental Gnosis. In this respect he diverges from European Rosicrucians. In his work he merely juxtaposed borrowed formulas rather than synthesizing them: Thelemic slogans beside Catholic prayers, runes beside Egyptian invocations. His frequent appeals to the Pistis Sophia as “Book of Books” are largely gestural; he never engages with its complex cosmology with exegetical rigor. Biography shaped doctrine. His childhood in a mining milieu, his encounters with indigenous healers, his medical practice, and his political adventures in Mexico all left their mark. The therapeutic orientation of his Mass — the prayers for signs, the testimonies of healing — mirrors his medical and folk-religious experience. His antimaterialism, his moralistic tone, and his rhetoric against “the world and its philosophies” reflect his revolutionary engagements. The missionary fervor with which he sought to spread the F.R.A. across Latin America is also biographically grounded. The resulting portrait is double. Krumm-Heller was indeed eclectic and at times fragile, a compiler whose rituals often resembled patchworks of borrowed symbols. But he was also an original innovator where he transformed his personal trajectory into a healing Gnosis — Christ-centered, sacramental, and Latin American in tone. His Mass cannot be reduced to a mere imitation; it is its own creation, even if marred by inconsistency and ideological ballast. His personality was that of a charismatic, polemical, politically entangled, and syncretic hierophant, whose strength lay in missionary fervor and whose difficulty lay in his struggle to weld his collages of ideas into a coherent doctrinal edifice. But perhaps this was precisely his strength: in the Latin American countries of his time, Krumm-Heller enjoyed strikingly greater success than contemporaries such as Reuss, Crowley, and many others. |

On-line Articles on the Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua |

|---|

Regarding Mexico read also this correspondence. A gallery of protagonists and documents. Texts by Arnoldo Krumm-Heller (This section is under construction.)

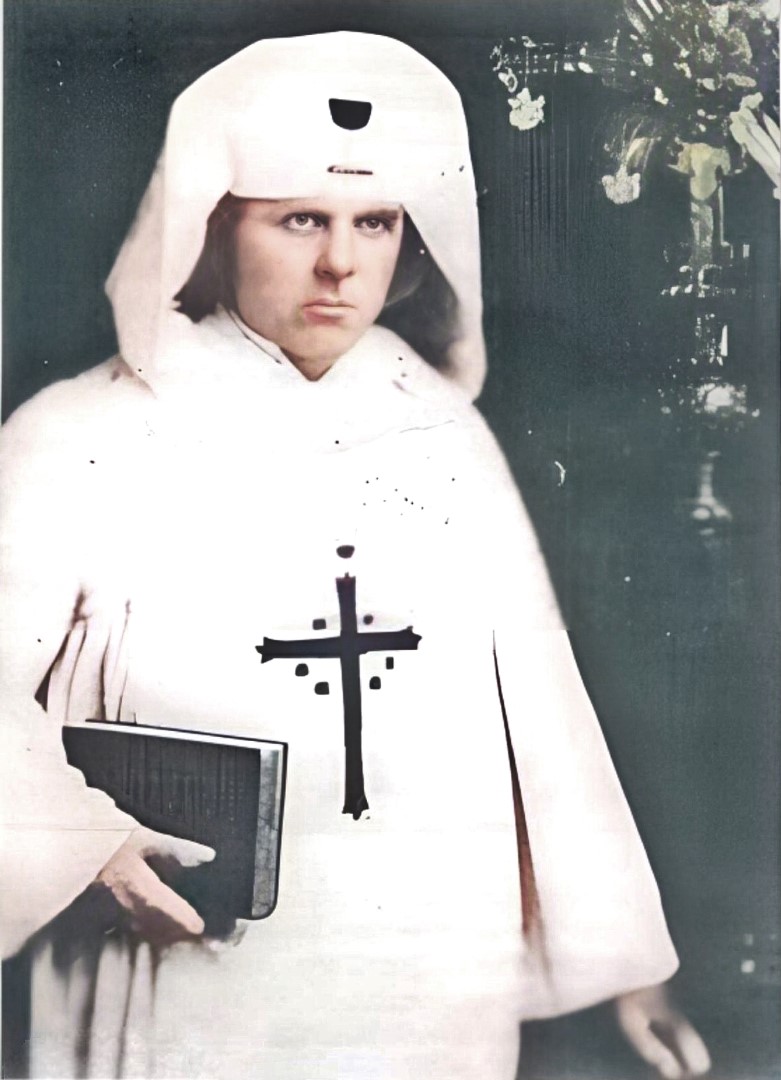

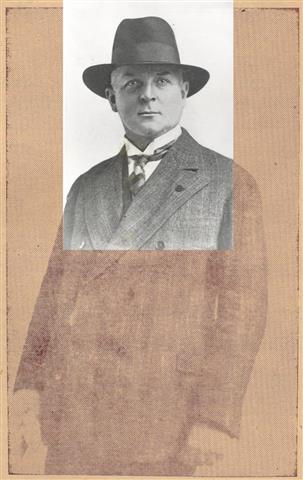

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller in 1918. [AI-colourized photograph]

|

Books on the Fraternitas Rosicruciana Antiqua |

|---|

|

|

|

My intent is to mirror puzzle pieces of the O.T.O.-phenomenon. If you have annotations, corrections, suggestions or complaints do not hesitate to contact me: mail |

|

|

|